Note: this article uses total fertility rates, which are only projections of how many children a woman might have during her lifetime, based on current age-specific birth rates. It is only actually possible to know how many children a cohort of women will have in retrospect, once the cohort is past its childbearing years. That is called the completed cohort fertility rate, which can differ from the total fertility rate to a significant extent. Total fertility rates can therefore be misleading.

If constraints of wealth and health ever become dramatically reduced, would fertility rates still remain below replacement levels?

—

In a short period of time (relative to the length of human history), a tiny difference in fertility rates can lead to an enormous difference in population. If for example there were to be a sustained average fertility rate of 2.15 children per mother, the world’s population could reach about 70 billion by the year 3000*. Yet a slightly lower average fertility rate, of 2.05 children per mother, could bring the world population down below one billion – back to mid-19th century levels – over that same span of time. Keep extrapolating to the year 4000 and this minuscule difference in fertility rates would determine whether our population falls back into the millions or rises improbably (or impossibly) to the trillions.

Put another way: if you were to extrapolate the current total fertility rates of the Dominican Republic (approximately 2.15) and Jamaica (2.05), then about two thousand years from now the world could have billions of Dominicans but only hundreds of Jamaicans

(*Hypothetically. And depending on a few other factors as well, such as infant mortality rates, average lifespans, and the ratio between male and female children. And assuming I didn’t bungle that math).

Obviously, fertility rates in the future won’t be the same in all places and all times. But considering the decisive effect that even a 0.1 difference in fertility rates could have over the course of a single millennium, it seems interesting to consider what fertility rates might become in the future, if the recent relationship between rising levels of wealth and falling numbers of children were to break down.

—

During the past fifty years, the world’s fertility rate has fallen from an average of approximately 4.6 children per woman in 1972 to an average of 2.3 children per woman today. In the next few years the world’s average may reach replacement levels (~2.1, in countries with low infant mortality rates and a relatively balanced ratio between boy and girl children) outside of Sub-Saharan Africa, where fertility rates are currently estimated to be 4.7. Even some of the most conservative of wealthy societies, such as American Mormons or Gulf-monarchy Arabs or religious (but not Orthodox) Israeli Jews, are approaching or have already reached replacement levels.

Many countries now have fertility rates as low as 0.8 (South Korea, the world’s lowest) – 1.8 (France, Europe’s highest). Fertility rates in the US and Brazil are both around 1.7. In Japan and much of Europe they are around 1.4. China’s fertility rate is somewhere between 1 and 1.7 (but probably closer to 1), down from 2.7 when it began its one-child policy in 1979, and down from 6 a decade before that, during the middle of the Cultural Revolution. India’s fertility rate is roughly 2.2, down from 5.2 when its own mass sterilization program began in 1975. Northeast China, China’s rust belt, a region of 110 million people, may have a fertility rate as low as 0.55!

To a certain extent, the relationship between high income and low fertility has already begun to break down. Northeast China, a relatively poor part of what is still a relatively poor country, is only the most extreme example of this. Many of the world’s medium-income and low-income countries now have fertility rates that are nearly as low as, or lower than, those in rich countries. With the exception of Sub-Saharan Africa and a few small Pacific island states like Samoa, only two countries, Afghanistan and Yemen, remain above a 3.5 fertility rate.

Even in Africa, 16 countries’ fertility rates are thought to have fallen below 3.5. Ethiopia, the second most populous African country, is estimated to have a fertility rate of 3.9. The world’s biggest outliers by far are Nigeria at 5.2 and the Democratic Republic of the Congo at 5.8; they rank third and eighth in the world in fertility rates, respectively. Yet even they are now down to where the world’s average fertility rate was in the 1950s. (Nigeria’s official population size, of about 235 million, may also be overstating its actual population size by many tens of millions of people. It’s not actually known how many people live in Nigeria; the country’s censuses have been politicized). Niger, a country with a much smaller population than Nigeria or the D.R. Congo, may now be the world’s lone holdout above 6.

That is still much higher than any rich country, of course. Apart from Israel, where the fertility rate is 3, no high-income country now has a fertility rate that is above 2.2. And even Israel’s is mainly due to Arab-Israeli and especially Ultra-Orthodox Jewish populations. The secular Israeli Jewish fertility rate is only 2.2, and it was below 2 for most of the 1990s and 2000s.

—

All this is remarkable, but it does not necessarily tell us what the future may hold; certainly not the long-term future. Just as fertility may be falling in part because of how expensive kids are – in terms of time, money, real estate, food, physical exertion, etc. – it could perhaps become higher again if humanity eventually becomes richer in all these things. If we are lucky and the future is one of abundance, in health and in wealth and in the time to spend both, it could plausibly result in an abundance of children as well, at least in comparison to today’s levels.

To put it somewhat simplistically: if we were all multi-millionaires, what would our average fertility rate be?

The obvious place to look for clues here is at the current fertility rates of the world’s richest people. But there are a few snags. I wasn’t able to find any estimates for the current fertility rates of millionaires or billionaires. (There is some good information on the topic of income and fertility here though, in an article by the demographer Lyman Stone). But even if those numbers were easily searchable, they still would not be proof of what might happen if everyone in society were rich. Today’s rich often became so by being workaholics. Even the heirs and heiresses with inherited wealth probably feel pressure to emulate their fortune-building parents or grandparents and the rest of society around them. Whereas if almost everyone in society was rich, societal values could perhaps shift to a certain extent away from work, and towards family-building.

At the moment however, there are no such societies. The richest economies in the world today, like Norway or Switzerland or Alberta or the Gulf Arab mini-monarchies, are nowhere near being ultra-rich. All of their average incomes are well under 100,000 dollars, and that money is of course not evenly distributed throughout their populations. The two major Gulf monarchies, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, have fertility rates of roughly 1.4 and 2.2, respectively. (The minority of the Gulf states’ population who are actually citizens, rather than migrant workers, have higher fertility rates, between 2 and 3). Norway and Switzerland both have fertility rates around 1.5. Alberta and Saskatchewan, where after-tax incomes have been very high and housing has been cheap (by Canadian standards), have fertility rates between 1.5 and 2, which is high for Canada but still below replacement levels. Nearby South Dakota, a high-income, low-cost-of-living state, has the highest fertility rate in the US, at 2. Texas has the highest of any large state in the country, about 1.8.

Still, it may be worth keeping in mind that most parents who have only one child would usually prefer to have at least two, but hold back only because of major constraints having to do with wealth or health. If you were to lift those constraints, it is not hard to imagine that a 2-child family would become the norm, or that families with 3 or more children would become very common again as well.

Even today, among people who are parents in their forties in the US, nearly twice as many have 2 children as have only 1 child. (In Europe, by contrast, roughly half of all families with children are 1-child families). 41 percent say they see 3 or more children as ideal, though admittedly that is just a poll. Considering these preferences, it is not impossible to imagine a rich country getting back to above the replacement rate*. Especially if there continue to be significant advancements in birth science, or if there are economic changes that make it easier for most people to afford fertility treatments, childcare, or housing.

The Israeli example might be somewhat instructive here. Not only is the 6.5 fertility rate of Ultra-Orthodox Israelis arguably made viable (as many secular Israelis will tell you) by the fact that the rest of Israeli society is wealthy enough to subsidize it, but even the secular Israeli Jewish fertility is slightly above replacement levels. This might be partly a result of nationalism, given recent Jewish history and Israel’s sense of embattlement. Nevertheless, if Israel today can have a fertility rate of 3, and secular Jewish Israelis 2.2, then we cannot rule out that future countries far richer and more technologically advanced than Israel could have above-replacement fertility rates too.

—

A century from now, things are going incredibly well, as you can see by the nice picture above. Our population has fallen back below 6 billion for the first time since the 1990s. People have healthy and delicious food and drink, childcare and medical care, supportive communities and loving families, good health well into their senior years, effective fertility treatments, cities where children and adults no longer risk getting crushed to death by automobiles, maybe even (if we’re really lucky) cheap high-quality lab-grown meat and long-range electric aircraft. Each person has at least 1000 square feet of housing for themselves. China has become liberal, America economical. The whole world has become rich and peaceful, and we have stopped massively polluting and harming natural environments.

Life is good; surprisingly good, considering all the dangers and damages we faced and caused in the preceding centuries. But the fertility rate has recently reached above replacement as a result of this success, for the first time in several generations. It’s reached above 2.1; it might even be inching up towards 3, back to where countries like the US and Canada were in the 1960s, or Israel and Saudi Arabia were in the 2010s. People really love having kids, it turns out. Lots of people are having lots of them. Even in this magnificent future, Malthus’ question remains: will population growth eventually outpace our ability to provide ourselves with that growth’s necessities? And how rapidly might it do so?

—

Maybe these aren’t actually such dismal questions. There are worse things to worry about than what to do about overpopulating utopia: we’ll be lucky if we get there in the first place. But it is interesting to consider that even in this best-case scenario — assuming that more outlandish outcomes such as outer space expansion are either impracticable or undesirable — our economic success might lead relatively quickly to a point where it becomes self-limiting. Hopefully, at some point before this scenario occurs, whether in this century or later ones, we will manage to live very well with one another, and with animals and other living things, while having fertility rates at or below replacement levels.

—

Additional Notes:

- Replacement-level fertility rates are higher in countries with high infant mortality, or which practice sex-selective abortion in favour of boy babies. In rich countries the replacement-rate is estimated to be 2.1, with about 0.3 of that 2.1 being the result of infant mortality and 0.7 being the result of there naturally being more boys born than girls. Currently, for the world as a whole, the replacement rate is estimated to be 2.25 children per mother.

- *Imagine a country where 55% of women have 2 children, 15% have no children, 20% have 3 children, 9% have 4 children and 1% has more than 4 children. This imaginary country would have a fertility rate just above 2.1. Or imagine that 40% of women have 2 children, 30% have 3 children, 20% have no children (which is roughly the rate in the US and Canada today, which are among the countries where childlessness is most common), 9% have 4 children and 1% have more than 4 children. Again, that’s a fertility rate just above 2.1. Does anything like these breakdowns seem likely to happen in the real world? Maybe not. (And obviously there will not actually be any countries where 0% of mothers have only one child). But I think this thought experiment might help show that getting back above replacement levels is not so far-fetched that it can be ruled out.

You could of course also look for the real breakdowns from countries that are above replacement rate today, or were above it in the past, to get a sense of what a plausible above-replacement distribution might look like. Indonesia, for example, is estimated to have a 2.1 replacement rate today. The US last had above-replacement fertility levels in 2006-2007, and before that in 1971. I looked for, but couldn’t find, the family size data for these cases.

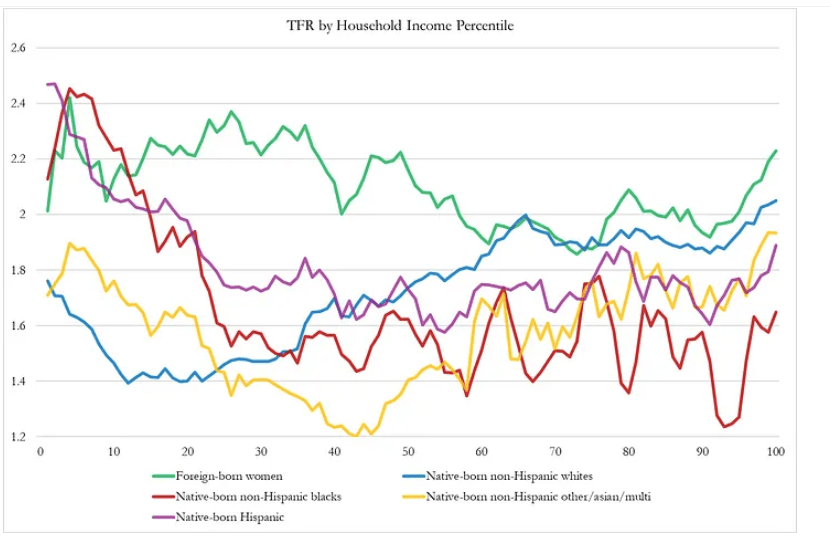

- This chart above, from the demographer Lyman Stone, shows age-specific fertility rates in the US over time. Not surprisingly, it shows that the big drops have been for young people: 25 year olds started having a lot fewer children in the 1960s, 20 year olds had drops in the 1960s and again in the 2010s, and 15 year olds had a drop in the 1990s and 2000s. 30, 35, and 40 year olds meanwhile have been rising. And because people in their thirties and forties tend to have higher incomes than people in their teens and twenties, this is another specific case where people with higher incomes have higher fertility than people with lower incomes, in spite of the fact that the total fertility rate of the US has fallen while the country’s average income has risen.

- A few more charts from Lyman’s article, with his quotes:

US total fertility rates and income percentile, by group - Maybe a greater trouble arising in this sort of futuristic prosperity would be from a rising inequality of family size. A couple who has, say, 5 children, and then the 5 children average 2 children of their own, and then the grandchildren all average 2 children as well, could end up as an old man and wife in a clan with over 70 members. And this is not counting the dozens or even hundreds of great-great-grandchildren who they might live to see if they started having their children at a young age, or if they live to a very old age. Meanwhile, people who have no children, or just one child, might instead be part of the same small types of families that have become the norm in recent years and decades. It could therefore become very common for there to be huge differences in the numbers of living descendants that people have. Whether or not this would be a problem is interesting to imagine.

This type of inequality could also take place at the level of nations, if some places achieve very great prosperity earlier than others. This has already happened to a degree in recent decades, where countries like the United States now enjoy much higher levels of wealth and much higher fertility than countries like China. China’s fertility rates went from above those of the US in the 1990s to well below those of the US in the 2020s, even as China’s rapidly rising per capita wealth still greatly lags that of the rich world. This is also true for other countries in East Asia, such as Thailand, which today has a similarly low fertility rate (1.3) and per capita income as China (about $20,000, adjusted for purchasing power parity). In the future, something like this could perhaps happen to other countries in South Asia or Sub-Saharan Africa, if fertility rates fall even more than they are expected to in the poorest countries, or if they surprise everybody by reversing direction and rising again in the richest ones.

- Where nationalistic fertility efforts are concerned, it is the Hungarian government that has of late put forward the largest financial incentives to mothers in an attempt to push up its fertility rates. So far these efforts have been fairly unsuccessful – Hungary’s fertility rate is 1.5, and has not changed very much in recent years. But it is early days yet, and there has been a pandemic, and Hungary is not a very wealthy country. (Hungary’s wealthier neighbour the Czech Republic, which has had the fastest-rising fertility rate in recent years, has also been growing economically at a faster rate than Hungary or most other countries in Europe). If a richer country, or perhaps a more autocratic country, tried a similar trick, maybe the results would be different.

What might China do, for example, regarding its low fertility rates? China scrapped its urban one-child policy in 2015 in favour of a two-child policy, and then in 2021 raised that to a three-child policy. A month after that it did away with limits on childbirth altogether. But, as in Hungary, it is not clear that these policy changes have been having much of an effect thus far. Whether or not they or other future policies do work to increase the country’s fertility rate will be significant over the course of the next decade, as the younger of China’s two major population cohorts is currently in its thirties (roughly speaking). They still have at least a few years left in which to have kids.

Considering the even lower fertility rates of its richer neighbours like South Korea and Taiwan, it seems unlikely that China’s fertility is going to bounce back much any time soon. Still, we should not be too surprised if it does end up rising, especially if the Chinese government tries hard to make it do so. China still has a far larger share of its population living in rural areas than other countries in Northeast Asia do. China’s new parents today also very often have no siblings themselves, which means that even if they have two kids instead of just one, most of those kids will have four grandparents to help the new parents with childcare. These grandparents are also still relatively young. Most are in their fifties or early sixties rather than in their late sixties or seventies.

On the other hand, if the only children who are now contemplating becoming parents in China and other countries worry that they will be left having to financially provide for their own parents as they get older, they may decide to have fewer kids in order to save more money and have more time and energy available to do so.

- In China, and in India too, it might matter not just how many kids parents have, but also how many girls. In both China and India today there are more than 11 boys born for every 10 girls born. That is the highest gender discrepancy at birth in the world (apart from Liechtenstein, a village-sized country), in the two largest countries in the world. Yet obviously it is girls, not boys, who grow up to bear children themselves. Women also tend to live much longer than men. Even in China and India, despite the early prevalence of boys, there are only about 9 male seniors (65 years and older) for every 10 female seniors. In many countries there are twice as many elderly women (85 years and older) as men.

Will these gender discrepancies that exist in China and (northern) India change in the years ahead? It seems plausible that they will, whether because of economic development in India, policy shifts in China (during much of the one-child policy era that recently came to an end, for example, rural Han families were allowed to have two kids only if the first child was a girl; in other words, the policy straightforwardly promoted having an imbalanced gender ratio in favour of boys), or because population aging in China could increase the perceived value of girls, given that it will be daughters and nurses who will tend disproportionately to care for the growing number of elderly people. The government too might decide to work hard towards rebalancing the gender discrepancy, perhaps out of a concern that it will lead to social instability borne of wifelessness.

Wth modern fertility treatments, it is becoming easier and cheaper for parents to select the gender of the child they want; and to do so without resorting to sex-selective abortion. It is not inconceivable that a country could put in place incentives meant to reverse the gender ratio of babies from, say, 55% male (where China and India have been in recent years or decades) to 55% female. But with a population that is 55% female, you would only need a fertility rate of 1.8-1.9 children per mother in order to achieve replacement levels, rather than the normal replacement rate of 2-2.1. If you had a population that is 60% female (the reverse of what some regions of China and India had in recent decades), then the replacement rate would fall to as low as 1.6-1.7. (Going full sci-fi, an 100% female society with no infant mortality could have a replacement level as low as 1). Of course, having such an imbalanced gender ratio might also contribute to reducing the fertility rate – there would be fewer potential dads around – partially offsetting the population-growth impact of there being more women.

(In most countries, by the way, an average of about 52.5% of babies born are male, due to natural causes; boys however also have higher child mortality rates than females do, especially in the poorest countries. In Nigeria for example, an estimated 53% of newborns are male, but only about 51.5% of 15-24-year-olds are male).

- Relatedly, average lifespans and health in general also matter to the population growth question. Though they have no direct exponential growth impact, as fertility rates do, they can have a linear impact: more old people can mean more people alive at one time. Perhaps more importantly, they could indirectly influence fertility rates. If you expect to live a long, relatively healthy life, you might become likelier to have more kids than you otherwise would.

True, this has not happened in countries like Japan or South Korea, which have among the highest average lifespans in the world, but low fertility rates. But Japan and South Korea are also extremely urbanized and densely populated, their populations tend to work long hours, and they are not close to being among the very highest income countries, in nominal or purchasing power-adjusted terms. Nor, perhaps, are their lifespans yet as long or as healthy as they will become in the future.

Today, the average lifespan in China, India, and Africa is 77, 70, and 64, respectively, whereas many high and medium-income countries have average lifespans of 80. (Japan is #1 at 84.3, the US is #40 at 78.4). If the world average lifespan were to rise from 72.7 today to 88 (which is the current average lifespan of women in Japan), that could lead to a significant increase in the world’s population over time, if fertility rates do not continue falling.

- As for the worry that the most extreme religious groups will keep up their extremely high fertility rates – sorry to bring up Ultra-Orthodox Israelis again, but their fertility rates are higher than even any country in Sub-Saharan Africa – I don’t know how likely it is that these high fertility rates will actually manage to be sustained over the course of the coming generations. It would take a number of generations of extrapolating current demographic trends for a religious population like the Ultra-Orthodox to become a majority of the population in a country like Israel, and before that happens it is perhaps more likely that economic developments will help make ultra-religious people have lower fertility rates than they do today.

Fertility rates among the most religious groups could fall because of increased exposure to secular society, or because of economic scarcity within the rapidly growing ultra-religious population. (Not for nothing was Malthus a clergyman). This scarcity could occur in absolute terms because of rapid population growth within the religious group, but it could also grow in relative terms, when compared to increasingly wealthy secular societies.

Invoking the Israeli example one final time, one can see that all of this has probably already been happening in recent years. Religious fertility rates have been falling, the amount of exposure to secular society within religious society has been rising, and economic scarcity within religious society has in many cases been rising both in absolute terms and relative to the increasingly wealthy secular or religious (rather than ultra-religious) populations.

- Perhaps the extreme scenarios that are likelier to occur in the future are ones that take place on the smaller scale of the religious cult, rather than the larger scale of an entire religious movement. A cult, whether of the new-age or old-school variety, could decide to try to use the (hypothetical) wealth and technology of the future to try and have as many children as possible, for as many generations as possible.

I don’t know how likely this actually is, but if for example a new fertility cult of, say, 1000 couples each were to have ten children over the course of three generations, it would grow to more than 120,000 members (assuming nobody were to leave the group or die during this time, and that new spouses could be brought into the group in each generation). Add an unlikely fourth generation into the mix and those 1000 original couples would have grown themselves a city-sized cult, with over a million members, to preside over in their elderhood. A hyper-natalist cult of this sort could also purposefully select for female children, in an attempt to rapidly reproduce. Again, I don’t think anything like these scenarios are likely either. But then, I would have also found unlikely many of the 19th and 20th century cults or new religions that really did come to pass.