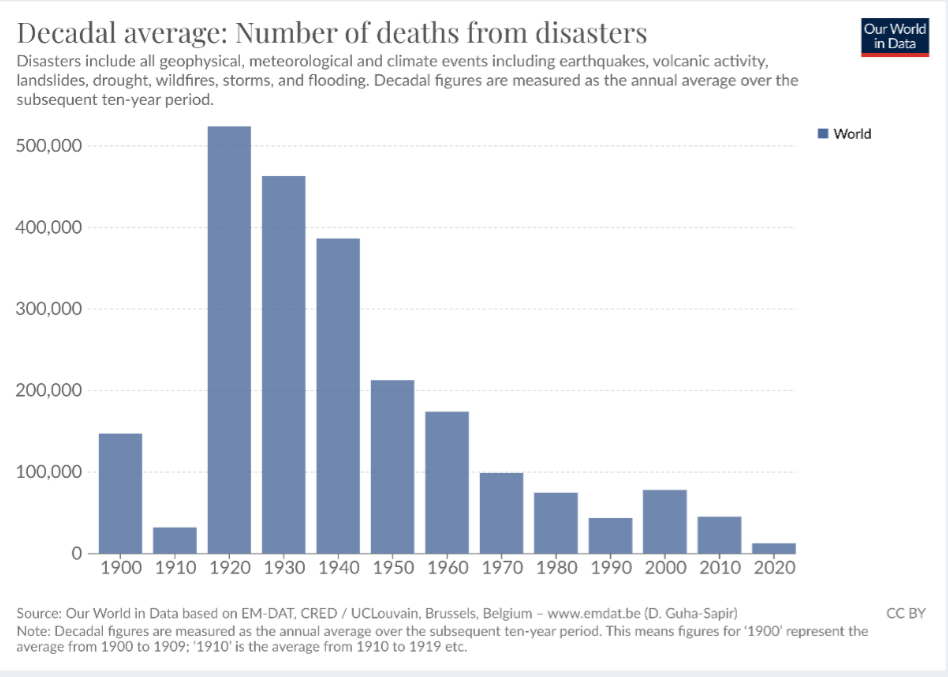

Leaving aside Covid-19, no single natural disaster in the past decade caused more than 50,000 deaths*. In the past two decades however, at least eight natural disasters have done so. The deadliest of these was most likely the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004, which caused an estimated 230,000 deaths, most of them in Indonesia but many also in Sri Lanka and other countries in the region. This was followed by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake (~87,000 deaths), the 2008 Burma cyclone (~138,000 deaths), the 2008 Sichuan earthquake (~88,000 deaths), the 2010 Haiti earthquake (~46,000-316,000 deaths) and a heat wave, drought, and wildfires in Russia in 2010 (~56,000 deaths). An earlier heat wave in Europe in 2003 resulted in an estimated 70,000 deaths.

*This may no longer be true. The recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria have caused approximately 45,000 deaths in Turkey thus far, and several thousand deaths in Syria

One obvious pattern here is the destructiveness of earthquakes and earthquake-triggered tsunamis. They caused four out of these eight disasters, including the two deadliest.

Financially too, earthquakes have usually been the most devastating disasters. The most expensive natural disaster in modern history was the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, which caused approximately 20,000 deaths (very few of which were due to the Fukushima nuclear disaster, which the tsunami triggered) and resulted in an estimated 400+ billion dollars worth of damage, adjusted for inflation, according to Wikipedia. (The 2010 Northern Hemisphere heat waves, if viewed as being a single natural disaster, may have been even costlier). That same year, the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand cost an estimated $44 billion, itself one of the most expensive modern-day disasters. The second most expensive disaster was another Japanese earthquake, in 1995 in Kobe (~6,400 deaths; ~$330 billion worth of damage). Third costliest was the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, China (~88,000 deaths; ~$176 billion).

The five most expensive natural disasters apart from these earthquakes may all have been hurricanes in America, each one taking place since 2005 (Katrina); three taking place in 2017 alone (Harvey, Maria, and Irma). Yet even the 2017 hurricane season as a whole cost less than either of Japan’s big earthquakes.

—

A good source on natural disasters is Vaclav Smil‘s book Global Catastrophes and Trends: The Next Fifty Years, published in 2006. It looks closely at the dangers posed by many different types of disasters, including low-probability, high-impact events like asteroid strikes, supernovae explosions, and mega-volcanic eruptions. According to Smil, the most common disasters of late have been floods and storms, but the deadliest have been earthquakes:

Of course, these do not come near the figures of the deadliest modern epidemics, not just Covid-19 or the Spanish Flu of 1918-1920, but also others such as the 1957-1958 Asian flu (~2 million deaths), the 1968-1969 Hong Kong flu (~1 million deaths), and the AIDS epidemic (~32 million deaths in its 60 years, for an average of 530,000 deaths per year, with a peak of 1.7 million deaths in 2004, most occurring in southern Africa). Nor do they approach the number of deaths from other horrible, avoidable problems, such as road accidents (~1.3 million deaths per year in recent years), indoor air pollution (~2-4 million deaths per year), or war (~30,000-200,000 deaths worldwide per year during the relatively peaceful past decade). They also do not come near the death tolls from the very worst natural disasters, like the floods that occurred in northern China in 1887 (~900,000-2 million deaths, perhaps half of which were caused by a resulting pandemic and famine) or in 1931 (~400,000-4 million deaths).

These lists of disasters do not include food crises or famines, the causes of which are often more political than environmental. The deadliest food crises to occur in recent years were the droughts in East Africa in 2011, which resulted in an estimated 50,000-250,000 deaths, and perhaps also in the Middle East in 2011 and 2012, which may or may not have been one of the causes of the Syrian civil war. The worst cases to occur in recent decades include the famines in North Korea from 1994-1998 (~240,000-3.5 million deaths), in Ethiopia from 1983-1985 during part of its civil war (~1.2 million deaths), and above all in China from 1959-1961 during the Great Leap Forward (~15-55 million deaths).

Obviously these Wikipedia statistics need to be taken with a large grain of salt. They often range widely: the death toll estimates for the recent 2010 Haiti earthquake, for example, run from 46,000-85,000 (according to a report made by the US Agency for International Development) to 160,000 (according to a University of Michigan study) to 316,000 (based on numbers from the Haitian government). The death toll from the 1976 North China earthquake, perhaps the deadliest post-WWII natural disaster, ranges from 240,000-650,000.

All of these estimates may also overlook indirect causes of death and destruction, and certainly they do not include the significant non-fatal consequences disasters usually cause. The 2015 Nepal earthquakes, for example, led to around 8,000 deaths, but 3.5 million people were made at least temporarily homeless by them. The heat waves in Europe and Russia in the 2000s killed tens of thousands of people, but many of those who they killed were already seriously ill. The 2011 earthquake and tsunami and nuclear disaster in Japan led not only to death and destruction directly, but also to increased pollution from coal and lignite, as it caused Japan and Germany to shutter most of their nuclear power plants.

Historically speaking, northern China and Japan have suffered some of the deadliest earthquakes, though in China’s case this has had more to do with the country’s population density and other factors than with the intensity or frequency with which it tends to experience earthquakes, which has generally been lower than that faced by Japan and other countries along the Pacific rim. Before the terrible earthquakes in Sichuan in 2008 and Hebei in 1976, there was the Gansu-Ningxia earthquake in 1920 (~273,000 deaths). Three years after that, the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake in Japan caused ~100,000-143,000 deaths, destroyed large parts of Tokyo and Yokohoma, and was, at the time, probably the most destructive disaster experienced by a modern industrial city. Possibly the deadliest ever earthquake occurred in Shaanxi, in northern China, back in 1556, killing an estimated 100,000-800,000+ people.

Along with the 1976 Hebei earthquake, the other deadliest disasters in the late twentieth century were the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone (~140,000 deaths), the 1975 typhoon and resulting collapse of the Banqiao Dam in central China (~230,000 deaths) and the 1970 East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) cyclone (~500,000+ deaths). That East Pakistan cyclone, which is likely the deadliest cyclone to have ever occurred, may also have triggered Bangladesh’s war of independence the following year. The cyclone struck just one month before Pakistan’s first ever democratic election was held at the end of 1970, and the poor flood-relief efforts by the Pakistani military government in the immediate aftermath of the cyclone is thought to have helped influence a large majority of Bengalis to vote for the Bengali nationalist Awami League. This in turn led to an alleged genocide being carried out by Pakistan against Bengalis, and ultimately to a brief but deadly war being fought between India and Pakistan.

—

Bangladesh and the Philippines are notable here, as being arguably the most prone to natural disasters, of various kinds, of any large countries. The Philippines in particular regularly experiences earthquakes, tsunamis, cyclones, and volcanic eruptions. Even as Bangladesh suffered one of its deadly cyclones in 1991, in the Philippines that same year the eruption of Mount Pinatubo, just outside of Manila, killed 847 people and caused “the largest stratospheric disturbance since the Krakatoa eruption in 1883, dropping global temperatures and increasing ozone depletion”, according to Wikipedia. It was the second largest known eruption in the twentieth century, trailing only the eruption of Novarupta in Alaska in 1912.

At least ten times greater than these eruptions however was the Mount Tambora explosion in Indonesia in 1815, the only volcano in recorded history other than Krakatoa to result in a death toll above 30,000. The Tambora eruption is estimated to have killed 70,000-250,000+ people, mostly through its impact on the global climate: it may have caused the famines of the “Year Without a Summer” in the Northern Hemisphere in 1816. Nearby Krakatoa too killed most of its victims indirectly, by triggering what may have been the third deadliest tsunami in recorded history (~36,000–120,000 deaths). The only deadlier tsunamis were caused by the Indian Ocean earthquake in 2004 and by the Messina earthquake in Sicily in 1908 (~75,000-123,000 deaths).

Going back all the way to Mount Vesiuvus’ destruction of Pompei and Herculaneum in 79 AD, only ten volcanic eruptions are estimated to have killed more than 10,000 people — a far lower figure than the number of deadly earthquakes, storms, or famines. Since Krakatoa in 1883 there have been only two very deadly eruptions, one in Colombia in 1985 and the other on the Caribbean island of Martinique in 1902. The Martinique eruption killed all but two of the 28,000 inhabitants of the town of Saint-Pierre – one of the survivors a prisoner in a jail cell who had been arrested the previous night. The Colombia eruption resulted in an estimated 23,000 deaths, and led to the creation of the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program in the United States, which six years later helped evacuate 75,000 people from around Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, keeping the death toll from that much larger eruption low.

Two months before the eruption in Colombia, which was the deadliest natural disaster in Colombian history, Mexico experienced the deadliest disaster in its history, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which caused an estimated 5,000-45,000 deaths. A number of other disasters in recent decades have had death tolls within a similar range. These include earthquakes in Gujarat, India, in 2001 (~13,000-20,000 deaths; India’s current prime minister Narendra Modi became Chief Minister of Gujarat that year, following the perceived inability of his predecessor to handle the aftermath of this earthquake), in Turkey in 1999 (~17,000 deaths; Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose government bears much of the responsibility for the high death count in last year’s earthquake, was released from prison the month before the 1999 earthquake, after having been mayor of Instabul from 1994-1998), in Iran in 1990 (~35,000-50,000 deaths, not long after the end of the Iran-Iraq War), and Armenia in 1988 (~28,000 deaths, not long after the start of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War).

Apart from earthquakes, the list of modern-day disasters with death tolls in this range also includes cyclones in Central America and Mexico in 1998 (~11,000 deaths), Bangladesh and India in 2007 (~15,000 deaths) and southeastern India in 1977 (~10,000-50,000 deaths), and flash flooding and landslides in Venezuela in 1999 (~10,000-30,000 deaths).

The United States, in contrast to these countries, has been mostly spared from deadly natural disasters. The Great Galveston hurricane in 1900 was the probably the deadliest disaster in American history, resulting in the deaths of 8,000-12,000 people. Heat waves in 1901, 1936, 1980, and 1988 may each have resulted in 1000-10,000 deaths. And the country does face a significant risk from earthquakes, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. (This Pulitzer-prize-winning New Yorker article about this topic is worth reading). Thus far however the deadliest earthquake the US has experienced, in San Francisco in 1906, resulted in a relatively low number of deaths (~700-3000). The next deadliest, in Alaska in 1946, caused 165 deaths. Alaska then experienced the world’s second-highest-magnitude earthquake of the past century, in 1964 – a magnitude 9.4 – which caused 143 deaths.

—

Like Alaska, certain places in the world have been struck repeatedly by large earthquakes. The most notable of these may be Valdivia, in Chile. It experienced the most powerful earthquake on record, in 1960, an earthquake so powerful that by itself it accounted for roughly 25 percent of the world’s seismic energy released in the 20th century. (The next two biggest in the century, in Alaska and Sumatra, together accounted for roughly another 25 percent). The first big earthquake recorded in modern times was also in Valdivia, in 1575, according to Wikipedia.

The next three big ones after that, all in the 1600s, were in Chile as well, including one in the capital, Santiago. Valparaiso (in central Chile, near Santiago) was then hit with big ones in 1730 and 1822, and Conception (on the coast between Valdivia and Valparaiso) in 1751 and 1835. More recently, the Chilean coast south of Valparaiso was struck by a magnitude 8.8 earthquake in 2010. It was 500 times more powerful than the earthquake Haiti had suffered through a month earlier, but, with only 500-550 casualties, it was hundreds of times less deadly.

The other area to flag in this regard is the island of Sumatra, in Indonesia. It has been hit with one of the only two recent earthquakes with a magnitude of at least 9; namely, the deadly Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004. (The other magnitude 9+ earthquake was the costly Japan earthquake in 2011; until then most experts had not believed that an earthquake above 8.4 was even possible in Japan). Before that, no 9+ magnitude earthquakes had occurred since Alaska in 1964 or Chile in 1960. A magnitude 9 earthquake is about 33 times more seismically powerful than a magnitude 8, and over 1000 times more powerful than a magnitude 7. Sumatra was also hit by three of the only four recent earthquakes in the magnitude 8.5-to-9 range (in 2005, 2007, and 2012; the fourth was Chile’s in 2010). Before 2004, there were no magnitude 8.5+ earthquakes since Alaska in 1964.

Going further back into human history, Sumatra also has the honour of being where Mount Toba erupted, around 75,000 years ago, in an explosion at least a dozen times greater than even Tambora’s was in 1815. The Toba catastrophe theory “holds that this event caused a global volcanic winter of six to ten years and possibly a 1,000-year-long cooling episode. In 1993, science journalist Ann Gibbons posited that a population bottleneck occurred in human evolution about 70,000 years ago [with fewer than 10,000 humans left alive in the world], and she suggested that this was caused by the eruption.” This theory is still debated today. It may serve as a reminder – as if we needed another one – that it pays to keep an eye on all the things that can go disastrously wrong in the world.