With the new year starting, it is now forty years since 1979. Forty is a biblical number, which is fitting because 1979 was a year in which religious belief proved to be decisively political. Some of these events are still well remembered: Iran’s Islamic Revolution, the Christmas Eve invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union, the Camp David Accords between Jimmy Carter, Anwar Sadat, and Menachem Begin. Other key events however are often forgotten, so that 1979 does not usually get the acknowledgment it deserves as being a year of unmatched religious and political action.

The year began with the resumption of diplomatic relations between the US and China, on New Year’s Day, ending three decades of formal estrangement between the two countries. This was followed by Deng Xiaoping visiting the White House at the end of the month, the first time a Communist leader of China had ever made such a trip. The new relationship had an immediate political impact when, on January 7th, the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia fell to the invading Communist Vietnamese. Five weeks after that, China invaded Vietnam, launching a short but brutal war against Vietnamese forces that had been fighting the US military only six years earlier.

According to Wikipedia: “On January 1, 1979, Chinese Vice-premier Deng Xiaoping visited the United States for the first time and told American president Jimmy Carter: “The little child [Vietnam] is getting naughty, it’s time he got spanked”. On February 15, the first day that China could have officially announced the termination of the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance, Deng Xiaoping declared that China planned to conduct a limited attack on Vietnam. The reason cited for the attack was to support China’s ally, the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia, in addition to the mistreatment of Vietnam’s ethnic Chinese minority and the Vietnamese occupation of the Spratly Islands which were claimed by China. To prevent Soviet intervention on Vietnam’s behalf, Deng warned Moscow the next day that China was prepared for a full-scale war against the Soviet Union; in preparation for this conflict, China put all of its troops along the Sino-Soviet border on an emergency war alert, set up a new military command in Xinjiang, and even evacuated an estimated 300,000 civilians from the Sino-Soviet border. In addition, the bulk of China’s active forces (as many as one-and-a-half million troops) were stationed along China’s border with the Soviet Union”.

While the political importance of China and America re-establishing a relationship is obvious, its religious significance has tended to be overlooked. It has however helped lead to one of the largest increases in any religion in modern history: the re-adoption of Christianity by many tens of millions of Chinese since the 1970s. In 1979 China’s Three-Self Patriotic Movement church was legalized by the Chinese government. It and many other much smaller churches have been so successful in the decades since that today China and America have probably the two largest Protestant populations in the world. China’s overall Christian population is difficult to estimate, but 50-100 million is a common guess. (Chinese Christians or semi-Christians, notably Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, and Hong Xiuquan, played an outsized role in the country’s history in the 19th and 20th centuries).

Of course, it was in the Middle East where the biggest religious and political upheaval in 1979 took place. In Iran, the Ayatollah came to power on February 11th, the Shah having fled to Egypt three weeks earlier. In a foreshadowing of the larger hostage-taking that would occur in Iran at the end of the year, on February 14th the US ambassador was kidnapped and killed in Kabul, Afghanistan, while on the same day Iranian militants temporarily took control of the US embassy in Tehran, kidnapping a Marine there.

On March 26, the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty was signed. Israel returned the Sinai peninsula to Egypt as part of the deal, while Egypt became the first Arab state to recognize Israel. It has proved to be an extremely successful deal, in that Egypt and Israel had fought four wars against one another in the three decades preceding it, yet have not fought a single war against one another in the four decades since. The three men involved in the deal, Jimmy Carter, Anwar Sadat, and Menachem Begin, had been the most supportive of religion among the top political leaders of their respective countries, generations, and faiths.

The month ended on a less peaceful note in a different arena of religious and political conflict: Britain. On March 30 Airey Neave, the Tory party’s Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, was assassinated outside of the British Parliament by a car bomb planted by Irish militants. The assassination took place just two days after a no-confidence vote had brought down a Labour government. Margaret Thatcher was elected Britain’s first female prime minister a month later.

This assassination would be followed by an even larger attack later in the year. On August 27[1], the Provisional Irish Republican Army killed eighteen British soldiers with two roadside bombs in Northern Ireland, while on the same day killing Lord Mountbatten (an uncle of Prince Phillip, who had formerly been head of the Royal Navy, head of the Armed Forces, and Viceroy of India), his grandson, and two others by planting a bomb on his boat[2].

A month later, Ireland would host its own biggest religious event in decades, when the Pope visited the island. The Pope was welcomed by a crowd estimated to include 2.7 million people, nearly the entire population of the Republic of Ireland[3].

This however was not the Pope’s most important trip abroad in 1979, nor the one to attract the largest crowds. John Paul II, who had only become Pope at the end of 1978 (a rare “year of three popes”), was the first non-Italian Pope in 450 years. He was, even more importantly, Polish, at a time when Poland was the largest country in the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. The Pope’s visit to Poland in June of 1979, often referred to as the nine days that changed the world, was the first trip by a Pope to a Communist country. It is thought to have played a meaningful role in the rise of the Polish Solidarity movement the following year – and the crackdown against it from 1981-1983 – and so in turn arguably helped end the Cold War.

The Pope’s influence also attracted enemies. When, at the end of 1979, the Pope was visiting Turkey, a young man named Mehmet Ali Agca, who was then beginning a life sentence in prison for killing the editor of a liberal Turkish newspaper earlier that year, escaped from jail and fled to Bulgaria. Two years later Agca shot the Pope in St. Peter’s Square. (Six months after that, martial law was declared in Poland, to restrain Solidarity). Given Bulgaria’s position in the Warsaw Pact and the role that Pope John Paull II played in Cold War politics, many people speculate that the Soviet Union was behind this attack in some way.

(Actually, Agca himself later claimed the KGB was involved. But he has a track record of making untrue, self-aggrandizing statements, so this does not prove anything decisively).

According to Acga, the Pope had orchestrated the siege of the Grand Mosque of Mecca, an event which was taking place when Acga made his jail break in November of 1979. This siege, which lasted for two weeks at the holiest site in Islam, was carried out by several hundred gunmen, perhaps as many as 600, led by a former Saudi National Guardsman, Juhayman al-Otaybi. Otaybi’s father and grandfather had fought against the Saudis fifty years prior in the Ikhwan revolt. His brother-in-law, Muḥammad bin abd Allah al-Qahtani, led the Grand Mosque siege alongside Otaybi, and was claimed to be the mahdi, a messianic figure.

Their attack took place on the first day of the new millennium of the Islamic calendar (1400 A.H.), toward the end of the annual Hajj pilgrimage. It is thought that there were initially 50,000 worshippers inside the building, but most were released early on during the siege. Saudi forces finally ended the siege after a number of poorly managed attempts and hundreds of deaths, by secretly enlisting the help of France, which sent three of its Special Forces soldiers to Mecca. They quickly converted to Islam in order to enter the holy city, then used gas to sedate many of the gunmen, who by then had taken refuge in the catacombs beneath the Mosque. The siege was finally ended by Saudi forces, and perhaps also Pakistani forces, storming the building.

The siege arguably had a major impact on Saudi culture and foreign policy, and a direct legacy in future events such as the emergence of Al Qaeda. It is a sad, fascinating story worth reading about, one that is often forgotten due to the Iranian hostage crisis, which had begun several weeks earlier and was consuming much of America’s attention instead. The siege remains an overlooked or misunderstood subject within much of the Muslim world as well, in part because the Saudis have been somewhat successful at hushing it up.

At the time, the siege had a number of immediate consequences, owing partly to confusion as to who had orchestrated it. As we have already seen, Acga claimed the Pope was involved. Many others believed that the United States was behind the siege. (The newly victorious Ayatollah Khomeini, for example, said in a radio address that “It is not beyond guessing that this is the work of criminal American imperialism and international Zionism”). This resulted in the destruction of US embassies by mobs in Libya and Pakistan on December 3. Others believed Shia revolutionaries in Iran were behind the siege. This may have led to an uprising in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, where the country’s Shia minority population lives and most Saudi oil is located. People there had been attempting to celebrate Ashura on November 25, the major holiday for Shia that has been mostly prohibited in Saudi Arabia.

(Ashura was also prohibited in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Today the pilgrimage to Karbala in Iraq, which is held at the end of the 40 days of mourning that follow Ashura, is probably the largest annually held pilgrimage in the world, attracting approximately 20 million people per year).

A week later during that same Ashura, Iran held a referendum to ratify the constitution of its new Islamic Republic, which Khomeini had declared following his success in an earlier referendum held in March. The two referenda had large voter turnouts and overwhelming results in favour of Khomeini’s position.

Less than a year after the Eastern Province uprising in Saudi Arabia, a kind of mirror-image event occurred involving Iran’s Khuzestan province. Khuzestan is Iran’s most oil-rich region; it is located on the Gulf coast next to Iraq and Kuwait and is inhabited primarily by Iran’s Arabic-speaking minority population. In 1979 a Khuzestan uprising took place during the Iranian revolution. Then, in May of 1980, a six-day siege of Iran’s embassy in London was carried out by Iranian Arabs – trained and organized, allegedly, by Iraq – to publicize their demand of sovereignty for Khuzestan.

According to Wikipedia, “The Special Air Service (SAS), a special forces regiment of the British Army, initiated ‘Operation Nimrod’ to rescue the remaining hostages, abseiling from the roof and forcing entry through the windows….The operation brought the SAS to the public eye for the first time and bolstered the reputation of Thatcher’s government…The SAS raid, televised live on a bank holiday evening, became a defining moment in British history and proved a career boost for several journalists…”

This is not to be confused with the much longer US embassy hostage-taking, in and by Iran, which was still going on at the same time. The famous, failed Delta Force and CIA rescue attempt ordered by Jimmy Carter had taken place only ten days before the SAS’ mission in London.

Shia-Sunni and Arab-Persian political relationships were also deteriorating elsewhere in the Gulf region during 1979, part of the process that helped lead to the most deadly war in the recent history of the region, the Iran-Iraq War, which began with Iraq’s invasion of Khuzestan on September 22, 1980.

At the start of 1979, Iraq and Syria had been discussing the possibility of unifying their armed forces and merging into a single state[6], to counter Egypt’s new relationship with the US and Israel. The Shia Islamic revolution in Iran however created the possibility of a closer relationship between Iran and Syria. Syria’s government, led by Hafez al-Assad and the country’s minority Allawite (a branch of Shia Islam, sort of) coastal elite, was at the time fighting Sunni groups such as the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. Syria also had interests in the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), a religious sectarian war in which Shia forces – a few years later emerging as the Party of God, Hezzbolah – were being energized by the Iranian revolution as well as by Israel’s invasion and subsequent withdrawal from Shia-inhabited South Lebanon in 1978.

In Iraq the reverse situation existed. The Iranian revolution frightened Iraq’s Sunni elite, in part because a majority of Iraq’s population were disenfranchised Shia. There had already been an unsuccessful uprising by Shia in Iraq in 1977, as well as an Iraqi Kurdish uprising in 1974-1975, which took place during an earlier, smaller Iran-Iraq War. This was followed by larger Shia uprisings in Iraq during 1979, triggered by the Iranian revolution. These may have played a role in leading Saddam Hussein, then the vice president of Iraq, to replace his elder cousin Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, the president since 1968, with al-Bakr’s resignation on July 16, 1979.

A week later Saddam carried out his infamous public purge of Iraqi politicians, claiming they had been plotting with Syria to overthrow the government of Iraq. The following April, he ordered the execution of Iraq’s Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al Sadr (whose posthumous son-in-law, the Shia cleric Muqtada al Sadr, is today arguably the most influential politician in Iraq), along with the Grand Ayatollah’s sister Amina, before beginning an eight-year war against the ayatollahs in Iran in the fall.

(Muqtada al Sadr’s father, the Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Muhammad-Sadiq al-Sadr, was also assassinated by the Hussein regime, in 1999. And Musa al Sadr, another highly prominent member of the extended Sadr family, who founded the Shia Amal movement and militia in Lebanon, disappeared in 1978. It is thought that Muammar Gaddafi may have had him killed).

Several weeks before Saddam’s coup, the Aleppo Artillery School massacre took place, one of the key events in a six-year conflict between Syrian Sunni Islamists and Hafez-al Assad’s government. This conflict intensified in November 1979 (the same month as the Siege of Grand Mosque in Mecca), with the arrest of Shaykh Zain al-Din Khairalla,”a leading voice amongst Islamists and a regular leader of Friday prayers in the Great Mosque of Aleppo”. This led to the Siege of Aleppo in 1980 and Hama massacre in 1982, in which several thousand or tens of thousands of people were killed (depending on which sources you believe). It may have also led, a generation later, to the Syrian civil war’s especially tragic war zones in Aleppo and the Hama-Homs region — and to 52 years now of rule by the Assad dynasty.

1979 was also the year in which Israel first attempted to prevent a rival country, Iraq, from developing nuclear power. In April, in southern France, Israeli agents used explosives to sabotage a reactor that was about to be shipped to Iraq. A little over a year later, in Paris, they assassinated an Egyptian scientist who was leading Iraq’s nuclear programme. Several months after that, in September 1980, Israel assisted the Iranian air force in its partially successful attempt to destroy Iraq’s nuclear reactor near Baghdad during the second week of the Iran-Iraq War. Finally, Israel attacked the Iraqi reactor directly in 1981.

Iran too carried out a significant assassination in Paris in December 1979, killing Shahriar Shafiq, a son of the Shah’s twin sister. Shafiq had been the highest-ranking royal in the Iran military, and the last to leave Iran during the revolution. In Paris in 1980, the Iranians also attempted to kill Shapour Bakhtiar, the last pre-revolutionary prime minister of Iran. He had been an opponent both of the Shah’s regime and of Khomeini. That attempt was a failure, but they later did assassinate him in Paris in 1991.

The year ended with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on Christmas Eve [7]. Two days into the war the Soviets killed their former ally, Communist Afghan President Hafizulla Amin [8], who had come to power following a revolution and coup in 1978 (along with Babrak Karmal and Nur Muhammad Taraki; Taraki was overthrown by Amin three months before the Soviet invasion, and assassinated). US president Jimmy Carter then signed the order for the CIA to provide lethal aid to the Afghan mujahedeen. Carter had already signed off on providing financial aid to anti-Soviet factions in Afghanistan earlier in the year.

Most of this aid was facilitated by the Pakistani regime of general Zia ul Haq, who had come to power in a coup at the end of 1977, and who had briefly strained relations with the US by overseeing the execution by hanging of Pakistan’s previous leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in April 1979. (Bhutto’s daughter Benazir and son-in-law Asif Ali Zardari later became Pakistani leaders as well; Benazir was assassinated in 2007). More than any other politician, Zia would be responsible for transforming the Pakistani state into a theocratic government.

The decade-long resistance of the mujahedeen against the Soviets and their allies would result in the deaths of perhaps 500,000-2 million people, including 15,000-25,000 Soviet soldiers. For comparison, Soviet forces suffered perhaps only 1000-2000 deaths fighting abroad in the post-WW2 decades preceding the Afghan war (most in the 1950s in Korea and Hungary).

Thus it can be seen that 1979 was also a turning point in the extremely violent Cold War. From a time of “national malaise” in the US (to reference the famous speech by Carter that year[9]), which was dealing with an energy crisis, a hostage crisis, and recent memories of Vietnam[10], 1979 would set in motion forces that would lead to a US victory over the Soviet Union ten years later. But then, it would also lead the US to its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, at the start of another new millennium.

1979 was significant because of its mix of religion and politics, but that mix was obviously was not new at the time, and has not gone away since. What may be more relevant is that the events of 1979 helped to shape the views of a generation of people who, today having reached positions of seniority, can now shape events themselves[11]. Perhaps this has contributed to the fact that American relationships with Iran and Russia remain hostile just like they were in 1979, while American relationships with countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt remain cooperative just like they were in 1979. True, there are signs that some of these relationships may be beginning to change. But for today at least, 1979 remains a guide worth remembering.

Notes:

[1]This attack took place just as a public debate over whether or not it was appropriate to satirize religion was taking place in Britain, as ten days earlier the Monty Python movie The Life of Brian was released. The movie was banned in the Republic of Ireland until 1987.

[2]Another prominent figure assassinated in 1979 was Park Chung-hee, who had been the president of South Korea since 1963, first coming to power in a military coup in 1961. He was shot by his own close friend, the head of Korea’s intelligence service. This in turn led to a series of coups in South Korea in 1979 and 1980. Park’s daughter was recently president from 2013 to 2017, but was then impeached, and served four years in prison on corruption charges.

[3]Two weeks before the Pope’s visit, Ireland passed the Health Act, which legalized the selling of contraception for the purposes of family planning. In China, meanwhile, 1979 was the year the one-child policy was implemented. (This was preceded, in China, by a plummeting birth rate during the 1970s, and, in India, by a mass forced sterilization campaign of poor men during the 1970s).

[4] A second serious attempt on the Pope’s life took place the following year (1982), at a pilgrimage to Fatima, Portugal, which he was making to give thanks for surviving Acga’s attack. There the Pope was stabbed by a traditionalist Catholic, Spanish priest with the bayonet of a rifle. The priest accused the Pope of being a Communist agent (somewhat ironic, considering that many accused Acga of the same). The Pope survived both attacks, and went on to have the longest papal tenure (1978-2005) of any pontiff other than Pius IX (1846-1878).

[5] According to one source: “Saudi intelligence services apparently had no accurate blueprints of the Grand Mosque, and knew nothing of the underground labyrinth where many of the militants took shelter; they eventually received plans to the site from Osama bin Laden’s older brother…While the official death toll was 127 soldiers, 117 militants, and an unknown number of civilians, independent observers reported a toll of ‘well over 1,000 lives.’ At least two-thirds of those killed in the siege were Iranians. The surviving insurgents were captured by Saudi authorities and all of the surviving male radicals were beheaded.” (I don’t how accurate these figures are, particularly regarding the number of the siege’s Iranian casualties. The details of the whole affair remain relatively uncertain).

[More recently, the Saudi Binladen Group was banned from construction work in Mecca following by far the deadliest crane collapse in history, at the Grand Mosque on (coincidentally) September 11, 2015, ten days before the Hajj, which resulted in more than 100 deaths, nearly all of whom were foreign workers from South Asia or Egypt. The Hajj itself then ended up being far more deadly still, as more than 2400 pilgrims attending (nearly 500 from Iran) were killed in history’s worst stampede – beating out several other morbid records set during previous modern Hajjes – due to horrendous crowd-management planning. This occurred less than a year into Salman’s kingship, and during the 2015 oil crash]

[6]Like Syria and Egypt had done from 1958 to 1961.

[7]Though not in Orthodox countries like Russia, where Christmas is on January 7. A decade later, on December 25, 1989, Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were tried and executed in Romania, about a month after the Berlin Wall was torn down.

[8]He was not the only Amin to be ousted from power in 1979. Uganda’s Idi Amin (no relation) was removed too, by an invading Tanzanian army.

[9]Though Carter never actually used the word malaise in the “malaise speech”.

[10]At the 1979 Academy Awards, The Deer Hunter won Best Picture while Jon Voight and Jane Fonda won Best Actor and Best Actress for Coming Home. Both were films about Vietnam. Apocalypse Now then similarly went on to win the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1979 (but was snubbed in favour of Kramer vs Kramer at the Oscars in 1980).

[11]In 1979, Donald Trump started building Trump Tower. Bill Clinton was elected governor of Arkansas at the age of 31. An 18-year-old Barack Obama moved to the US mainland to attend a liberal arts college in Los Angeles. Xi Jinping finished his degree in chemical engineering, as a “Worker-Peasant-Soldier student” in Beijing. Angela Merkel too was becoming a chemist in a Communist state, having finished her physics degree at the end of 1978 in Berlin. Mikhail Gorbachev was promoted in November 1978, moving to Moscow from Stavropol (near the Caucuses) to become the Party’s youngest Central Committee member, at the age of 49. Shinzo Abe finished his degree at the University of Southern California in 1979. Narendra Modi graduated from the University of Delhi in 1978 and began working for the Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization, the RSS, in 1979. Jeremy Corbyn entered politics as a local councillor in 1979; Boris Johnson, who recently beat Corbyn with the biggest vote share in any UK election since 1979, was (no surprises here) at Eton.

Additional notes:

- In 1979, Mother Teresa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- China has not really fought in a war since Vietnam in 1979

- The Taiwan Relations Act was passed in the United States, and remains in effect today

- From a recent article in Week in China magazine: “The handshake between Deng Xiaoping and Muhammad Ali in December 1979 was a ground-shaking moment in both sport and geopolitics. China had just reestablished diplomatic ties with the United States and the boxing superstar was visiting Beijing as a special envoy for then American leader Jimmy Carter. His job was to persuade the Chinese to skip the Moscow Olympics, which was scheduled for the following year. They did just that but sent a large delegation to the Los Angeles Games four years later – the first time for decades they had participated at the Olympics in a competitive and practical sense (a small squad of athletes made a symbolic appearance in Helsinki 1952). The message from Beijing seemed clear. China was turning away from the Soviet Union and more towards the US as it started to usher in a period of economic reforms and more openness to the outside world. Beijing even lifted a domestic ban on boxing as well.”

- The other major area of political conflict, Cold War rivalry, and religious activity was Central America, where wars in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua were taking place around this time. A key event in the El Salvador civil war (1979-1992) was the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, which took place while he was at mass in March 1980, a day after he had publicly asked Salvadoran soldiers not to carry out orders to kill civilians. In Nicaragua, meanwhile, where the Sandinistras overthrew the Somoza government in 1979, they did so with the support of the country’s Catholic clergy, an unusual – and short-lived – alliance between a left-wing revolutionary movement and the Church.

- From Wikipedia: [Hezbollah leader Hassan] Nasrallah studied at the Shia seminary in the Beqaa Valley town of Baalbek. The school followed the teachings of Iraqi Shi’ite scholar Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, who founded the Dawa movement in Najaf, Iraq, during the early 1960s. In 1976, at 16, Nasrallah traveled to Iraq where he was admitted into al-Sadr’s seminary in Najaf…. Nasrallah was expelled from Iraq, along with dozens of other Lebanese students in 1978. Al-Sadr was imprisoned, tortured, and brutally murdered. Nasrallah was forced to return to Lebanon in 1979, by that time having completed the first part of his study, as Saddam Hussein was expelling many Shias, including the future Iranian supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, and also Abbas al-Musawi. Back in Lebanon, Nasrallah studied and taught at the school of Amal‘s leader Abbas al-Musawi, later being selected as Amal’s political delegate in Beqaa, and making him a member of the central political office. [Amal was founded by Musa al-Sadr, who was disappeared in 1978]. Around the same time, in 1980, Mohammad Al-Sadr was executed by Hussein”. The current Prime Minister of Iraq, Muhammad Shia’ al-Sudani, was ten years old in 1980 when his father and five other family members were executed by the Iraqi government for having been members of the Shia Islamic Dawa Party. Muqtada al-Sadr currently leads the Iraqi Shia Sadrist movement.

- The Second Yemenite War was fought in 1979 between North Yemen and South Yemen, with various outside powers participating on each side. The war began following the assassinations, only two days apart, of the heads of states of both the North and South in July 1978. Ali Abdullah Saleh, who took over as president of North Yemen following the first of these assassinations, would later become the leader of a re-unified Yemen in 1990. Saleh would preside over a further civil war in 1994, and eventually be forced out of office in 2011 after the Arab Spring. He then became involved in yet another civil war, which began in 2014 and continues today. He was killed in the war at the end of 2017.

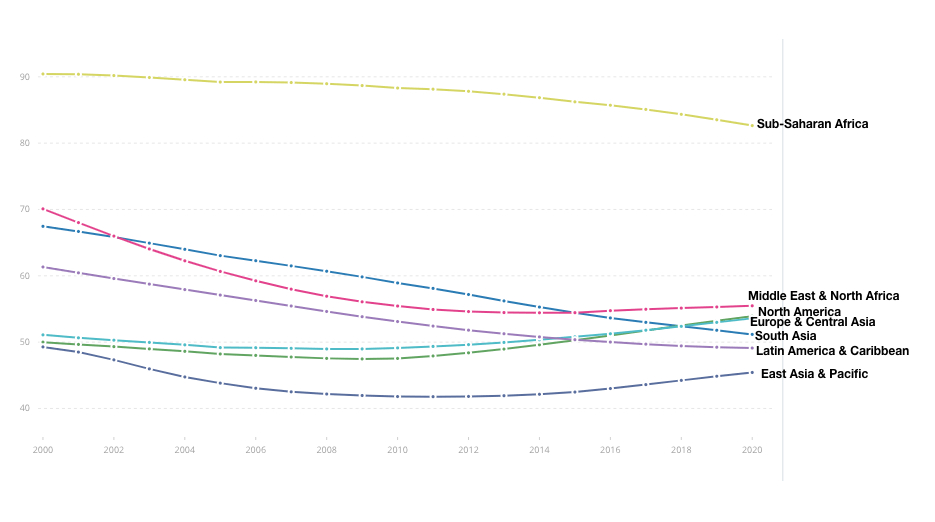

- Yemen is thought to have had the highest fertility rate in the world in 1979, at nearly 9 children per mother on average. Today its fertility rate is below 3 children per mother, a lower figure than that of perhaps 40 other countries.

- The 1970s was also the key decade for one of the major religious trends that has been taking place in the world in recent generations, namely the emergence of evangelicalism – and the relative decline in Catholicism – in Latin America, especially in Central America and Brazil.

- In December 1978, a few months after Argentina hosted and won the World Cup, Argentine military forces attempted to land on three remote, disputed islands Argentina shares with Chile at the southern tip of South America, but had to call off the landing because of bad weather. The Pope was then brought in to resolve the dispute, which was only successfully accomplished after Argentina’s military government lost power following its Falklands War with Britain in 1982 (which was fought over similarly southerly islands). As a result of this dispute, Chile supported Britain in the Falklands War. The military dictatorship in Argentina lasted from 1976 to 1983.

- The Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the most significant in US history, occurred in March, 1979 (twelve days after the movie The China Syndrome was released). Later, in July, according to Wikipedia: “The largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history, the Church Rock uranium mill spill, took place near Church Rock, New Mexico when a dam was breached, releasing the contents of a disposal pond maintained by United Nuclear Corporation….. The spill contaminated the water supply of much of McKinley County, New Mexico and Navajo County, Arizona within the Navajo Nation territory.”

- 1979 may have been the peak year for energy price inflation in the United States

- In India, Indira Gandhi was voted out of office in 1977 in the aftermath of the 1975-1977 Emergency, the first time a leader of the country’s Congress Party had failed to become prime minister. The incoming government tried to have Indira arrested and expelled from parliament, but in the subsequent election in 1980 she returned to power for a third time. That was the last of her election wins: she was assassinated in 1984 by two of her Punjabi Sikh bodyguards, after having ordered Operation Blue Star at the Golden Temple, the holiest Sikh site. Her son Rajiv took over from her and became PM in 1984 – an election season marked by large-scale anti-Sikh pogroms – but was assassinated as well, in a suicide bombing carried out by a member of the Tamil Tigers in 1991 (with assistance from two leaders of the Sikh Khalistan movement).

- In Turkey, according to an article in New Lines Magazine, “In 1980, after a decade of near civil war between left and right, the military carried out a violent coup and propagated the Turkish-Islamic Synthesis as a means of uniting the country. Three years later, the former World Bank economist and conservative, Turgut Ozal, became prime minister. This was the moment that neo-Ottomanism went from the mosque and the tea house to the government. Ozal’s Motherland Party (ANAP) represented — as Ozturk explains — the “merger of all the different colours of Turkey’s right-wing political tradition: conservatives, nationalists, and Islamists.”

- The group that Acga, and his co-conspirators such as Oral Celik, associated themselves with was called the Grey Wolves. It was a nationalist and pan-Turkist paramilitary organization that carried out attacks such as that which killed more than 100 Alevis (a mystical religious minority group) in December 1978. According to Wikipedia, “they are also alleged to have been behind the Taksim Square massacre in May 1977 [which killed an estimated 30-40 left-wing demonstrators] and to have played a role in the Kurdish-Turkish conflict from 1978 onwards”. The Grey Wolve’s leader, Abdullah Catli, might have also been involved in Acga and Celik’s murder of Abdi İpekçi, which landed Acga in jail, and perhaps even in Acga’s attempt on the Pope’s life in 1981.

- By coincidence, that murder of Abdi Ipekci took place on the same day that Khomenei returned to Iran after 15 years in exile in Turkey, Iraq, and (after 1978) France, February 1, 1979. And when Acga fled from prison later that year he escaped first to Iran, before ending up in Bulgaria

- All of the longest lasting presidencies in the world today began in 1979, in Africa: Angola’s Jose Eduardo dos Santos (who finally left office in 2017), Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea (still in power), and Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo (although with a brief stint out of office from 1993-1997)

- In a sense, all three of the key Abrahamic faiths were deployed in the Cold War in 1979: (Sunni) Islam in Afghanistan, (Catholic) Christianity in Poland, and the campaign to allow Jewish refuseniks, most famously Anatoly Sharansky, to emigrate from the Soviet Union. [Sharansky, like the plurality of emigrating Soviet Jews, came from Ukraine; he was born in Stalino, which was renamed Donetsk in 1961 and annexed to Russia by Vladimir Putin this past year].

- In neighbouring Bahrain, just off the coast of the Saudi Eastern Province’s capital city and major oil fields, Iran supported a coup attempt by the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain in 1981. Iran had long claimed Bahrain as a historical province of Iran, and Bahrain’s small population – only 350,000 in 1979 – was largely Shia, but ruled over by a Sunni monarchy. The coup attempted to place an Iraqi Shia ayatollah who was exiled in Iran, Hadi al Modarresi, in power in Bahrain. (Modarresi is still around today, in Iraq; he recently claimed Covid-19 is a divine punishment for Chinese dietary habits and mistreatment of Uighur Muslims. (Muqtada al Sadr, in contrast, blamed Covid on same-sex marriage legislation in various countries). During the Arab Spring in 2011, Saudi forces crossed the causeway that links the Eastern Province to Bahrain, to assist the Bahraini monarchy to suppress protests.

- In Israel, Menachem Begin’s Likud party came to power in 1977, ending three decades in office by leftist parties, which had governed since the country’s independence from Britain in 1948. Likud has been in power for roughly 28 of the 45 years since then, and right-wing parties generally have been in power for 35 of those years. Likud’s current leader [and now PM once again, in 2022], Benjamin Netanyahu, was Prime Minister for 15 years, from 1996-1999 and then from 2009-2021, narrowly beating David Ben Gurion’s previous record as the longest-serving Israeli leader. In 1979 Netanyahu was working at Bain Capital in the US, where he was a friend of Mitt Romney. Three years earlier, in 1976, when Netanyahu was in his final year as a student at MIT, Netanyahu’s older brother Yonatan led the raid on Entebbe in Idi Amin’s Uganda (a regime which lasted until 1979), and was the only one of the 100 Israeli commandos involved who was killed.

- Anwar Sadat, who, after ordering the surprise invasion of Israel on Yom Kippur (and Ramadan) in 1973, broke ground visiting Jerusalem in 1977 (just after Likud came to power) and signed the peace accords in 1978 and 1979, was assassinated in 1981, at an annual victory parade celebrating Egypt’s invasion of the Sinai in that earlier 1973 war. Hosni Mubarak, who as vice-president was sitting next to Sadat during the assassination, then become Egypt’s leader for the following three decades. Mubarak’s (brief) successor, Mohammad Morsi, joined the Muslim Brotherhood in 1979. His current successor, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, first became a military officer in 1977, just like Mubarak, Sadat, and Sadat’s predecessor Gamal Abdel Nasser had all been.

- In the roundup of hundreds of suspected religious extremists or alleged enemies of the state that followed Sadat’s assassination, one of the men arrested was a recent medical school graduate and Muslim Brotherhood member, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who had that same year worked at a Red Crescent hospital treating refugees in the border areas of north-west Pakistan. He would later become second to Osama Bin Laden in Al Qaeda. It is not clear whether or not he is still alive, but he would be 70 years old now if he is.

- Al-Zawahiri was also a supporter of the “Blind Sheik”, Omar Abdel-Rahman, who had issued a fatwa sanctioning Sadat’s murder and who, like Zawahiri, would be jailed for three years following the assassination. Abdel-Rahman would later be involved in attacks such as the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing, the massacre of dozens of tourists visiting Luxor in 1997, the murder of extremist Israeli politician and rabbi Meir Kahane in New York City in 1990, and the 1994 attack on Egypt’s most famous writer, Naguib Mafouz (for his allegorical novel about Abrahamic religions and modernity, Children of Gabalawi).

- Other events, notably the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979, in which perhaps 1000 people were killed, were also fundamental to the later creation of Al Qaeda. Arguably, the 9-11 attacks were themselves prefigured in the 1970s. In September 1970, four airplanes in Europe were hijacked on the same day by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, with three flown to Jordan and the fourth, an El Al plane, unsuccessfully hijacked as the pilot threw the plane into a nosedive. A day later a fifth plane was hijacked and flown to Jordan, the non-Jewish hostages on the planes were released while the Jewish hostages were kept imprisoned, and the Black September war began between the Jordanian government and militants from the Palestinian Liberation Organization (the latter backed to a certain extent by the Syrian government, which invaded northern Jordan during that brief conflict).

- In 1979, the Mossad assassinated the alleged organizer of the militant group Black September, Ali Hassan Salameh (the “Red Prince”), who was claimed to be behind attacks such as those at the Munich Olympics in 1972 and the assassination of Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Tal (who had presided over the Black September War) in 1971.

- From Wikipedia: “Israel invaded Lebanon again in 1982 in alliance with the major Lebanese Christian militias of the Lebanese Forces and Kataeb Party and forcibly expelled the PLO… Israel withdrew from most of Lebanon in 1985, but kept control of a 19-kilometre security buffer zone, held with the aid of proxy militants in the South Lebanon Army(SLA).” It held this territory until 2000.

- The Sabra and Shatila massacres took place at this time, in 1982, two days after the assassination of newly elected Lebanese President Bachir Pierre Gemayel, a Christian. The massacres involved the killing of several hundred or several thousand civilians, mostly Palestinian refugees or Shia Lebanese, by a Christian Lebanese militia, backed by Israeli forces that were surrounding the area, in the neighbourhood of Sabra and refugee camp Shatila.

- The following year, Israel’s Kahan Commission deemed that Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, among others, bore personal responsibility for the massacre. Wikipedia again: “Initially, Sharon refused to resign, and Prime Minister Menachem Begin refused to fire him. However, following a peace march against the government, as the marchers were dispersing, a grenade was thrown into the crowd, killing Emil Grunzweig, a reserve combat officer and peace activist, and wounding half a dozen others, including the son of the Interior Minister. Although Sharon resigned as Defence Minister, he remained in the Cabinet as a Minister without Portfolio. Years later, Sharon would be elected Israel’s Prime Minister [in 2001].”

- In 2002, one of President Gemayel’s closest associates, militia commander and politician Elie Hobeika, who had been involved in carrying out the Sabra and Shatila massacre (and whose own fiancee and much of his family was killed in an earlier massacre, the Damour massacre, perpetrated by a Palestinian militia in 1976; which was itself a response to still earlier massacres of Palestinians) was assassinated by a car bomb in Beirut, not long before he was scheduled to testify in a Belgian court about the Sabra and Shatila massacres.

- Less comedic than The Life of Brian, the film Khirbet Khizeh was also set in the Holy Land, and was also prevented from being shown. It was cancelled immediately before it had been scheduled to air on Israeli television, in February of 1978. Israel’s Ministry of Education and Culture prevented it from being shown – though the novella it was adapted from had been part of the Israeli curriculum at the time – because it depicted Israeli mistreatment and ethnic cleansing of a Palestinian village during the 1948 war. The controversy this censorship caused within Israel was soon after overshadowed by the invasion of southern Lebanon by Israel in March, as well as by the Coastal Road massacre – still likely the deadliest ever attack by Palestinians against Israelis – which also took place in March. And then by the Camp David Accords which began in September 1978.

- Rising ethnic and religious conflict in another part of the world at the end of the 1970s, namely in Sri Lanka between the predominantly Hindu Tamil and Buddhist Sinhalese, arguably led to the first post-WWII case of frequent suicide bombing, during the country’s long civil war that began in 1983. Suicide bombing had been extremely rare during the previous generation, but has been used with increasing frequency in the decades since. To this day Sri Lanka has experienced the most such attacks outside of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Two of these attacks, in 1996 and 1997, killed dozens of people in the World Trade Centre in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s tallest building – yet another prefiguring of the 9-11 attacks.

- Around the same time, in Lebanon, the 1983 Beirut barracks truck bombing, killing 241 American and 58 French military personnel, and 6 civilians, was also a key event in the reemergence of politically and religiously motivated suicide attacks, and might have contributed to the view within Al Qaeda that Western militaries might retreat from the region if aggressively attacked.

- Of the 19 hijackers involved in 9-11, 11 were born between 1977-1981 and all between 1968-1981.

- Having survived the attempts on his life in 1981 and 1982, Pope John Paul II later also avoided the 1995 Bojinka plot, a proto-Septemer 11 attack that came somewhat close to being carried out by Khalid Sheik Mohammad’s nephew Ramzi Youssef, in which the Pope would have been assassinated in the Philippines, 11 American airliners flying out of Asia would have been destroyed by concealed time bombs, and a hijacked or rented airplane in the US might have been crashed into the CIA headquarters or a skyscraper.

- In Iraqi Kurdistan, Masoud Barzani became the head of the Kurdish Democratic Party in 1979 upon the death of his father, and survived an assassination attempt in Vienna that year. Among other things, he would later be a central figure in the Iraqi Kurdish secession referendum in 2017.

- Syria, despite being a fellow Arab country and Ba’athist regime, backed Iran in the Iran-Iraq War, blocking Iraq from using its most important oil pipeline running through Syria to the Mediterranean. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab monarchies, however, supported Iraq financially, and at times so too did outside powers such as the US, France, and even the Soviet Union.

- Iran’s Khuzestan province is on the Mesopotamian, Gulf-Arab side of the Zagros mountain range, which runs along the Iran-Iraq border in every place except for Khuzestan. In this way too Khuzestan is arguably a mirror of Saudi Arabia’s oil-rich Shia-inhabited Eastern Province, which is separated from the majority of Saudi Arabia’s population by the Arabian desert. With the exception of Riyadh, most Saudi citizens live in the country’s far west or south-west, far from the Gulf coast.

- The Vela incident also occurred in 1979, which might have involved South Africa, or perhaps other countries such as Israel, Pakistan, India, or France, testing nuclear weapons.

- In the US, Baptist minister Jerry Fallwell Sr. founded the Moral Majority in 1979, a “key step in the formation of the New Christian Right” (according to Wikipedia).

- The “Satanic Panic” also began in the United States in 1979, following a series of three murders that took place in Fall River, Massachusetts

- In the Mormon church, the Revelation on Priesthood, announced in October 1978,

“reversed a long-standing policy excluding men of black African descent from the priesthood” - Cult activity in the United States also reached one of its high points in the late 1970s.

The main example of this is the “Jonestown massacre” in Guyana in November 1978, involving Jim Jones’ San Fransisco-based People’s Temple, in which over 900 people were either killed or committed suicide with poison and American Congressman Leo Ryan was murdered. But there were other prominent cases too, such as the Rajneesh movement (“Rajneeshpuram” was founded in Oregon in 1981), or the Nation of Yahweh, founded by Hulon Mitchell Jr., aka Yahweh ben Yahweh, in Florida in 1979. The Nation of Islam also experienced a revival of sorts at the end of the 1970s, under the newfound leadership of Louis Farrakhan. - “In 1978, the U.S. Congress asked President Jimmy Carter to designate [Menachem Mendel] Schneerson‘s birthday as the national Education Day U.S. It has been since commemorated as Education and Sharing Day.” Schneerson is considered a messiah by at least several thousand Jews in the Chabad movement worldwide.

- There was pushback against cult activity in these years too, notably the 1978-1979 lawsuit United States v. Mary Sue Hubbard et al., which ended in convictions of high-ranking members of the Church of Scientology, and the 1978-1979 Congressional investigation of The Unification Church of the United States. [The Unification Church recently gained attention for its possible, indirect role in motivating Shinzo Abe’s assassin in 2022].

- The late 1970s was an important time for the modern youth religions of superheroes, sci-fi-fantasy stories, and sports superstars. 1977-1983 was Star Wars. 1977-1982 was Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and E.T.: the Extraterrestrial. 1978 was the first big superhero movie, Superman. (Marlon Brando played his heavenly father Jor-El, a year before playing Kurtz in Apocalypse Now). 1979 was Ridley Scott’s Alien (followed up by Blade Runner in 1982) and the first Star Trek movie, and the publication of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. 1977-1981 was Steven King’s The Shining (both the book and the movie), the The Stand, and the beginning of the The Dark Tower series. 1977-1980 was the first trilogy of Tolkien film adaptations, and 1979 was the publication of Tolkien’s posthumous mythological cycle, The Silmarillion.

- On at least one occasion, this sci-fi film wave got closely mixed up with international politics. During the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 (as Ben Affleck’s Argo later made famous) a CIA operative made use of producer Berry Geller’s 1978 purchase of the rights to Roger Zelazny’s sci-fi novel “Lord of Light” – about human spacefarers who turn themselves into a sort of Hindu pantheon of gods on an alien planet – to set up a fake Hollywood studio in order to pretend to scout locations for a movie in Iran, and so rescue several escaped hostages who had been hiding out in the Canadian embassy. (In 1978, before the Iranian Revolution had happened, Geller had been hoping to turn the film’s hypothetical production site into an ambitiously imagined theme park, Science Fiction Land, once filming was complete, to help pay for the costs of making the film). The sci fi phenomenon of the preceding years was the reason why such a crazy-sounding plan actually seemed credible.

- In sports, 1979 was the rookie year of Wayne Gretzky, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, and Rickey Henderson. It was also the first year the NBA added a three-point line, and ESPN was founded. (Ditto CSPAN and, in 1980, CNN, the first 24-hour news channel). In boxing, it was the last year in which Muhammad Ali held a championship belt – he won it at the end of 1978 in what was, at the time, the highest-attendance boxing match in history. Sylvester Stallone, among others, was sitting ringside at that match; 1979 was also the year Rocky Balboa won his first fictional championship belt. (Raging Bull came out the following year, 1980).

- An American religion that is perhaps even bigger than sports or superheroes is that of pickup trucks and SUVs. The Ford F-150 has been the best selling vehicle in the United States since 1981, and the best selling pickup truck since 1977. This was also the peak period for road fatalities in the US, at about 50,000 per year on average during the late 1970s.

- In other TV news, 1979 saw the first ever biopic of Elvis (starring Kurt Russel) – 43 million Americans watched live. It also saw the last ever episode of All in the Family – 40 million watched live.

- In Canada, Pierre Trudeau was Liberal prime minister from 1968-1979 and again from 1980-1984, but was briefly out of power in 1979 after losing an election to the Conservative’s Joe Clark, who formed a minority government with the help of the Social Credit Party‘s seats in Quebec (the last time the Social Credits ever won a seat in parliament). All the provinces west of Quebec voted for Clark, but Quebec went heavily for Trudeau. The following year, the first referendum on Quebec sovereignty was held, initiated by the Parti Quebecois, which had won its first Quebec premiership in 1976. It voted roughly 60-40 “No” to the confusingly worded question the referendum asked its voters. A second referendum was held in 1995, with a much closer 50.6%-to-49.4% result.

- In Scotland and in Wales referenda were similarly held in 1979, on the question of devolution to a Scottish Assembly and a Welsh Assembly, respectively. The Welsh were a strong No (80%-20%, roughly); the Scots were a slim Yes (51.6%-48.4%), but because those Yes voters only accounted for 32.9% of total registered voters in Scotland, less than the 40% threshold the referendum rules required, devolution was not achieved. A Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Parliament were not created until 1999, following second referenda in Scotland and Wales in 1997 (this time with a slim Yes for Wales and a big Yes for Scotland).

- Joe Biden became a senator in 1973, two weeks after his wife and daughter were killed in a car crash. (He was then the sixth-youngest-ever senator. Now he is the oldest ever president). According to Wikipedia: “In his first decade in the Senate, Biden focused on arms control. After Congress failed to ratify the SALT II Treaty signed in 1979 by Soviet general secretary Leonid Brezhnev and President Jimmy Carter, Biden met with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to communicate American concerns and secured changes that addressed the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s objections. When the Reagan administration wanted to interpret the 1972 SALT I treaty loosely to allow development of the Strategic Defense Initiative (aka Star Wars), Biden argued for strict adherence to the treaty. He received considerable attention when he excoriated Secretary of State George Shultz at a Senate hearing for the Reagan administration’s support of South Africa despite its continued policy of apartheid“.